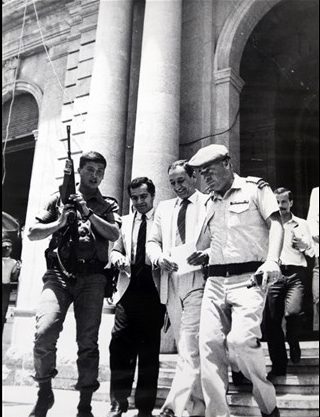

Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri listens to speeches during a session at the parliament in Beirut, Thursday, April 19, 2012. (The Daily Star/Mohammad Azakir)

Read original at The Daily Star

His Shiite community was long viewed as deprived and marginalized, neglected by successive governments after independence in 1943, both politically and in development projects, especially in the predominantly Shiite areas in Beirut’s southern suburbs.

For supporters, Berri is credited with boosting the Shiite community’s role in the country’s decision-making, helping them gain equality in power-sharing alongside Christians and Sunni Muslims.

As well as being the longest-serving politician in the highest position a Shiite Muslim can attain under the country’s sectarian-assigned ruling system, Berri also occupies the second highest office in government after the Maronite Christian allocated presidency.

At the age of 79, the green-eyed and white-haired Berri shows no sign of stepping down either as speaker or as leader of the Shiite Amal Movement, which he has headed since 1980. Also rare in a country of political dynasties, Berri has stated his intention not to hand his position to either his eldest son Mustapha or his most politically active son Abdullah, and has made no indication in recent years that this stance has changed.

“The main reason behind Berri’s success in keeping his post as Parliament speaker unchallenged for 25 years is the wide popular support he enjoys within the Shiite community as a result of the implementation of badly needed development projects and public services in the south and the Bekaa region,” a parliamentary source told The Daily Star. “At the national level, Berri’s moderate and conciliatory policies he had followed to shield the country from sectarian divisions have won him praise from various sects.”

The source added that Berri’s ability to forge both local alliances and attract regional backers has helped him maintain the country’s sensitive internal power balance “while keeping an eye on regional and international developments as a means to weigh his options at home.”

Berri has forged alliances with internal key players, most notably Hezbollah but also the Marada Movement as well as with less likely bedfellows such as the Future Movement and MP Walid Jumblatt’s Progressive Socialist Party. The strategic alliance between the Amal Movement and Hezbollah has helped the two parties capture all 28 Shiite parliamentary seats bar two in every election since 1992.

But his pragmatic, bipartisan approach has helped him secure his position not only as the unchallenged chief of the legislative body, but also as the undisputed leader within the Shiite community. His Ain al-Tineh residence is a regular fixture on the schedule of international visitors to Lebanon.

Even today, after more than six years of war in Syria, Berri’s firm alliance with Syrian President Bashar Assad appears as strong as ever; as are his ties with Iran – he attended the swearing-in ceremony of President Hassan Rouhani in August. As a link between regional powers and local factions, he has played a central role in naming presidents, forming Cabinets and approving administrative appointments.

Born into an immigrant merchant family in Sierra Leone on Jan. 28, 1938, Berri’s roots are in the southern town of Tibnin near the border with Israel. His meteoric rise to power started before he attended the Lebanese University in 1963 to study law.

After working as a lawyer, both privately and in the Court of Appeals, he found himself in the employ of charismatic Shiite spiritual leader and Amal Movement founder Sayyed Musa Sadr. A little over a year after Sadr’s 1978 disappearance in Libya, Berri took over Amal’s top post, succeeding Hussein Husseini who later preceded Berri into the speaker’s office.

With the 1975-90 Civil War already yearslong, Berri was also behind the military rise of the Amal Movement. As a resistance movement against Israeli occupation, Berri led Amal in spearheading the fight against the occupying force until the emergence of rival-turned-ally Hezbollah in 1982.

With Syria’s backing, the Amal and PSP militiamen, supported by a coalition of pro-Syria nationalist parties, staged an armed intifada (uprising) on Feb. 6, 1984, against President Amine Gemayel who was accused of negotiating a peace treaty with Israel and of monopolizing power in the hands of the Maronites. The uprising toppled the government of Prime Minister Shafik Wazzan before the end of the month.

Despite the two parties today appearing almost lockstep on policy, Amal fought a bloody battle against Hezbollah in the streets of west Beirut and across the south as the two sides struggled for dominance of the 1.2 million strong Shiite community. Syria intervened to broker reconciliation and an alliance between the two main Shiite parties. This alliance has generally endured despite occasional minor fights between supporters of the two sides.

Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri listens to speeches during a session at the parliament in Beirut, Thursday, April 19, 2012. (The Daily Star/Mohammad Azakir)

Berri and his Amal Movement are known to have intervened on many occasions to secure the release of Western hostages taken during the Civil War. Several hostages were even taken to Berri’s office in west Beirut’s Barbour neighborhood before they were whisked away to Syria en-route home. In 1985 the New York Times profiled “a soft-spoken, mild-mannered, 46-year-old lawyer” who had just helped free seven Americans taken hostage by Hezbollah on board TWA Flight 847 from Cairo to San Diego. At the time, the paper said Berri was “perhaps the most powerful man in Lebanon.”

The end of the war in 1990 and Berri’s appointment as speaker a few years later ended his time as a militia leader and Cabinet minister through the 1980s.

In the postwar Lebanese landscape, Berri helped keep a lid on rising sectarian tensions after Syria’s withdrawal from Lebanon in 2005 by convening dialogue sessions of all political leaders – including Hezbollah’s rarely seen in public leader Sayyed Hasan Nasrallah – in Parliament. These continued throughout 2005 up to the 34-day war between Hezbollah and Israel in July 2006.

Following the Feb. 14, 2005, assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, Berri and Jumblatt brokered an extraordinary Muslim electoral alliance. The Amal and PSP parties came together with the Future Movement and Hezbollah in a bid to protect the country from Sunni-Shiite strife caused by the seismic shifts that followed Hariri’s death. The alliance brought together both pro- and anti-Syrian groups at a time when the political parties were sharply dividing into the March 14 and March 8 blocs.

However, a few years later Berri was criticized by the March 14 coalition of the Future Movement and its Christian allies for refusing to convene Parliament for 18 months between November 2006 and May 2008, and for paralyzing the legislative body and preventing it from electing a new president at the end of Emile Lahoud’s term in 2007.

The decision came after Amal and Hezbollah resigned from Prime Minister Fouad Siniora’s government following a dispute over the Hezbollah-led March 8 alliance’s demand for veto power in government and the U.N.-backed Special Tribunal for Lebanon investigating the 2005 assassination of Rafik Hariri.

Then, as Lebanon teetered on the edge of a renewed civil conflict after Hezbollah briefly overtook west Beirut on May 7, 2008, Berri joined Jumblatt, then-Free Patriotic Movement head Michel Aoun and other major Lebanese leaders in Doha for talks to redraw the political balance.

The so-called “Doha Accord” led to Parliament’s election of then Army commander Michel Sleiman as a “consensus president” at the end of May 2008 and the formation of a national unity government. Berri stayed on his post as Parliament speaker, again unchallenged.

Despite his wartime legacy, Berri is known for taking a moderate approach to contentious political issues and his staunch defense of the Muslim-Christian coexistence in a multisectarian country.

During the presidential vacuum that endured until 2016 after Sleiman’s term ended in 2014, Berri hosted national dialogue sessions attended by rival leaders at his Ain al-Tineh residence in a bid to maintain stability and find solutions to the latest crisis. His proposal of a package deal that included a president, Cabinet’s formation and new electoral law was ultimately unsuccessful.

Separately, he also hosted several dialogue sessions at Ain al-Tineh in the past two years between senior officials of the Future Movement and Hezbollah aimed at defusing sectarian tensions fueled by the 6-year-old war in Syria.

However, critics say Berri made a major misstep in the lead up to Aoun’s Oct. 31, 2016, election. He long supported Marada Movement head Suleiman Frangieh, with some claiming that this was based on the assumption that Saad Hariri – who would return as prime minister after Aoun’s coronation – would never back the FPM founder for the presidency. Many point to Saudi Arabia’s presumed veto of Aoun’s candidacy as the basis for Berri’s calculation.

However, Hariri’s volte-face to support Aoun paved the way for his election and in a final solidification of the move, a high-ranking Saudi delegation visited Beirut a few days before a Parliament session that elected Aoun to meet with the FPM founder in what was viewed as a Saudi green light.

Since then the speaker and president have had a testy relationship – despite them both denying any bad blood – over several issues, from the electoral law to the recently passed salary scale.

Despite attracting his fair share of enemies and detractors as speaker, Berri has mostly been a rare unifying figure in a deeply divided political system. Through his 25 years of brokering, backroom dealing and horse trading, he has gained a well-deserved reputation for pulling rabbits out of hats to break political deadlocks during some of the most tense times in postwar Lebanon. – Reporting by Hussein Dakroub, Writing by James Haines-Young

Read original at The Daily Star